The 4 Elements of a Memorable Science Demonstration

Since starting at Steve Spangler Science in 2009, there’s one question that gets asked of our team more than any other: how do you create a memorable science demonstration? And the truth is, from our customer service team to our production team to Steve Spangler himself, we’ll all give you a different answer. So which answer is right? All of them!

Nobel Prizes for everyone! (Source: Wikipedia)

No matter who is supplying the formula for a memorable science demonstration, they’re correct. Every demonstrator uses the same 4 elements to create the perfect demo for their group, family, kids, or audience, though their methods may be different. They happen to correspond very well with the 4 classic elements. Most people start with…

Earth – Research

Earth – Research

Earth is the most familiar of the elements. We spend every day traversing its dusty, dry surface, but we have no clue what’s actually going on inside of it. For all we know, the core of the earth is a big, bubbling vat of baking soda and vinegar waiting to erupt with dyed carbon dioxide bubbles.

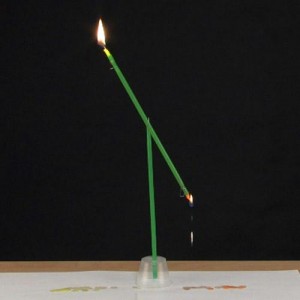

Science fair basics aside, it’s good to reacquaint yourself with the science behind the demonstration you’re going to perform. Even if you’re confident in your answer as to why you can create a teeter-totter by with two candles, it will be beneficial to get a refresher. Who knows, science could have uncovered a different answer!

Researching your demonstration is also a great opportunity to discover ways of taking your experiment further. Find ways to spin off of your initial demonstration. This is your chance to really find ways of driving your lesson home.

Water – Practice

More often than not, mysterious happenings come from the water. Flesh eating river fish, mythical monsters, and giant snakes make sure that no human (scientist or otherwise) ever gets too comfortable within a triple-jump of water’s edge.

You shouldn’t be too comfortable in the performance of your demonstration, either. No one (read: actually, literally no one) likes having their demonstration, presentation, slide show, or what-have-you fail to perform. Geysers that don’t explode, launchers that don’t launch, and paper airplanes that don’t do the “plane”-part are all sure-fire ways of winding up red-faced in front of your audience.

Now, this is science, so there’s always a chance that things just won’t go your way. THAT is what makes practicing your demo so valuable. Practice gives you the chance at troubleshooting possible issues with your demo. From setup to procedure to clean up, practicing makes sure you’re ready for anything that science throws your way.

Air – Application

Air – Application

Without air, we’re dead. That’s just a fact of life, and YES I intended that horrible pun.

We all require air to run our body. While you never forget how to breathe, we don’t think about it very often, unless we’re really USING our breath. Runner, yoga instructors, midwifes… these people know what it means to really use our breath, because they learned to apply it.

The same goes for so many science demonstrations and lessons. When our minds learn new information, like that hot air has low pressure and rises, we are much more likely to remember it with a direct application. Talk to them about how the downstairs of their house probably feels cooler than the 2nd story or talk to them about weather, wind, and pressure.

When demos don’t match up with a solid application, you create the dreaded, “When am I ever going to use this?” You need earth and water to be ready for that one!

Fire – Passion

Earth is solid, water is liquid, and air is gaseous. Fire is plasma? Fire is flame? Fire is part of a grouping of things called “intangibles” by sports coaches everywhere; just like passion.

Here we see the intangible ability of narcolepsy. (Source: Flickr)

Passion may not be absolutely required to pull off a memorable science demonstration, but it definitely aids in the effort. People of all ages can tell when someone is passionate about what they’re doing. The more genuinely excited you are about the demonstration you’re doing, the more excited your audience is going to be. Your energy is contagious.

Now just go and do it!

Fresh Prince of the Science Fair.

Fresh Prince of the Science Fair.

Writer for Steve Spangler Science.

Dad of 2. Expecting 1 more.

Husband. Amateur adventurer.

Expert idiot.

*I* actually do like it when a demo occasionally fails.

I completely agree that practice is essential when performing demos, and something that most of us don’t do enough. But I’d also add that when a demo doesn’t give the outcome we expect we should embrace these opportunities.

When it goes “wrong” you will have their undivided attention.

They are getting to see something unique. They are seeing the real you, as you cope with the situation. To an audience this is pure gold. They are almost always more interested in you than in your demo (unless you are doing something extremely emotionally engaging).

In fact, failure is so engaging that, as a science presenter, I often engineer one deliberate fail in each show.

If you’re interested, you can read more about the educational power of science demos in this article:

http://learn-differently.com/informal-educators/resources/in-defence-of-the-classroom-science-demonstration