White Winter Butter and Golden Summer Butter

By Jane Goodwin

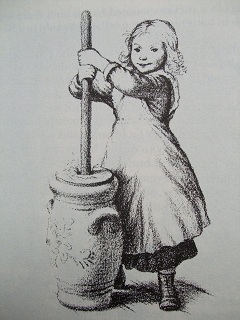

In Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House in the Big Woods – incidentally the first in the Little House series – Laura’s Ma churns the cream into butter once a week. Each day had its own work, in addition to the usual chores that had to be done every single day, and Thursday was churning day.

In summer, the cream, and the butter, were golden yellow, but in winter, the cream was white, and so was the butter. According to Laura, white butter wasn’t as pretty as golden butter, and since Ma wanted everything on her table to be pretty, she colored the butter in winter.

Ma did this by first shredding a large carrot as finely as possible, and putting the soft pile of grated carrot in a pan of milk. She heated the milk, and when it was hot enough, she poured the carroty milk into a clean cloth bag, and squeezed the bright yellow milk into the churn of white cream. Now the butter would be golden! (Laura doesn’t mention how that carroty butter tasted!) (Laura and Mary fought over who got to eat the hot, grated carrot dregs.) (A person can actually learn to cook just by reading the Little House books!) Ma then put all the butter through the molds, so each pat would be pretty, too.

In fancy cookbooks, a difference is made between recipes that use winter butter, and recipes that call for regular butter. It’s not just the color that’s different; it’s the texture and butterfat content, too.

What is the reason for white butter in winter and golden butter in the warmer months? It’s science.

Back in Laura’s day, cows roamed the woods and meadows in the warmer weather, eating fresh grass, flowers, fungi, and other fresh, moist things. In winter, the cows were confined, and fed dry hay. Pioneer-day butter was also made from “cultured” cream, which meant that the day’s milking was left untouched on a shelf at night, and in the morning, the cream, which rose in the night, was skimmed off the top and put into the churn. (The more cream skimmed, the skimmier the milk. If there were young children in the family, some cream was left to mix back into the skim milk.)

Few butters found in the stores today are made of cultured cream – it takes too long. Uncultured butter is still delicious, but to a gourmet, the difference is very noticeable. (If you’re not a gourmet, you probably can’t tell the difference on your toast.) It’s a fact, though, that many chefs prefer that pasty white winter butter so much, that they stockpile it in the freezer whenever they can get it.

Butter is, of course, made from cream, and cream is mostly butterfat. American butter must, by law, contain at least 80% butterfat – the remaining percentage is pretty much water. The most expensive French butters contain at least 86% butterfat, but that kind of butter is harder to find here. Uncultured butter also contains more lactic acid, which gives it a richer taste and a texture that blends more easily with various doughs.

After churning uncultured cream, you’ll get butter swimming in skim milk. After churning cultured butter, you’ll get butter swimming in buttermilk. (Check the label on that carton of buttermilk – you’ll see the word “cultured.” You won’t see that word on the butter you buy at the grocery.)

Your grocery store strives for standardization in its foods, and golden butter is the only kind most people have ever seen, so most chains buy butter from dairies that make their butter from grass-and-hay-fed cows. Americans also often assume that pale foods will be bland, not realizing that white butter is much richer than golden butter, both in taste and texture.

However, since winter butter is very hard to find in most places, most people will never see it, and will assume, all their lives, that all butter in all seasons is golden yellow.

We know better though, don’t we.

Making butter today is very easy, even if you don’t own a cow. Just buy some heavy cream at the store, pour it into a jar with a tightly-fitting lid, and start shaking. Shake until the fat separates and you see a lump of golden butter floating in the jar. Shake a few more times, and then remove the lid and pour the skim milk into another container. Wash and dry your hands thoroughly, then pick up the entire glob of butter, hold it over the jar, and start squeezing. You’re squeezing out much of the water that makes up a percentage of all butters. When the water stops pouring between your fingers, put the butter in a small bowl, sprinkle just a little salt over it, and blend with those clean fingers. Eat it now or put it in the fridge for later. As for the skim milk – drink it, or put it in the fridge to use later. That milk will probably be speckled with little butter dots, so it’s best used for cooking.

And now you know why Laura and Mary liked Thursday’s churning day almost as much as they liked baking day! (Baking day was Saturday.)

P.S. What color is your butter?

This is so interesting. I’m looking forward to reading the Little House Books with my girls and we will definitely try making butter this way when we do.

so cool

This worked so well! We all had fun doing this and eating the results! Great lesson to pull some science into our day.

I bought some butter recently in December that was white, slightly harder and bland tasting, and suspected that it had been aldulterated. Cultured butter in other words is “sour”. It is not as universal and feels “spoiled” when eaten by itself, on bread or with coffee. I even went as far as clarifying cultured butter to reduce the unpleasant flavor. It can be added to certain meals or pancakes with sour cream instead. In the industrial world with refrigeration butter should be sweet and fresh.