Science Fair Boot Camp – An Intense Training Program That's Changing the Science Fair Experience

Our blog editor (and my favorite contributor), Susan Wells, recently wrote an article about kindergarteners being banned from science fairs. Susan does a great job of reporting on science happenings that truly stike a nerve. In response to many of your comments, Susan asked if I would share an overview of a long-term research project that I’m working on with students, parents and teachers at one of our elementary school partners, Laura Ingalls Wilder Elementary in Littleton, Colorado. Grab a new cup of coffee and take a look…

Science Fair Boot Camp

Think about a real Boot Camp . . . intense training for a condensed period of time. The leader motivates, teaches, directs, trains, and models the behaviors or actions desired for the young recruits. Those young recruits learn discipline, critical thinking, planning, strategy, and organization. They also learn from their mistakes and work together to find solutions. Boot Camp is preparation for the “real deal.”

Now think about how this Boot Camp metaphor might be applied to science and elementary school “recruits.” At Wilder Elementary School in Littleton, Colorado, we started a Science Fair Boot Camp training program five years ago. Every year, every student in the school performs a science experiment in class, modeled by the teacher. We are mid-way through a seven year program and are seeing signs of great progress in our students and teachers.

In the Science Fair Boot Camp, the teacher models scientific thinking and the proper way to conduct a science experiment for his/her students. The program is based on the idea of “teachers do it first.” Over the years, scientific inquiry has generally not been modeled for kids. We know that many elementary school teachers do not have a science background, and the thought of conducting experiments and modeling “good scientific inquiry” is out of their comfort zone. It doesn’t have to be scary. This program provides engaging, hands-on, simple activities that kids love and teachers can model even if they haven’t had much science themselves.

We have found at Wilder that the teachers are growing as much as the kids. Despite some initial hesitancy, the staff is on board and excited about Boot Camp. What’s coming out of this program is stronger kids, but also stronger teachers. We’re focusing on teaching our staff how to teach science—they have to learn it themselves first and know it well enough to be able to explain it clearly to others. Many teachers learn best by teaching. Look back on the first time you taught something and how bad it may have been. Then consider how much you’ve improved over time as you’ve gotten more comfortable with the material and “tweaked” your classroom activities. That’s what is happening at Wilder. Our teachers are much better teachers of science because of the last couple of years of “tweaking” and improving what they do in this Boot Camp program.

We have found at Wilder that the teachers are growing as much as the kids. Despite some initial hesitancy, the staff is on board and excited about Boot Camp. What’s coming out of this program is stronger kids, but also stronger teachers. We’re focusing on teaching our staff how to teach science—they have to learn it themselves first and know it well enough to be able to explain it clearly to others. Many teachers learn best by teaching. Look back on the first time you taught something and how bad it may have been. Then consider how much you’ve improved over time as you’ve gotten more comfortable with the material and “tweaked” your classroom activities. That’s what is happening at Wilder. Our teachers are much better teachers of science because of the last couple of years of “tweaking” and improving what they do in this Boot Camp program.

The first key to engaging students in doing real science is to understand the difference between a science demonstration and a hands-on science experiment. Demonstrations are usually performed by the teacher and are typically used to illustrate a science concept. Science experiments, on the other hand, give participants the opportunity to pose their own “what if . . .?” questions. This inevitably leads to controlling a variable—changing some aspect of the procedure or the materials used to perform the experiment. If no variable exists, then you don’t have an experiment; instead, you are merely demonstrating something. It might be a very interesting or entertaining demonstration, but without a variable you can’t test anything.

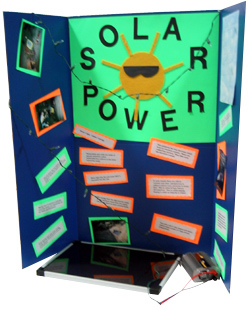

That’s where this Boot Camp program starts. The teachers at each grade level design a true science experiment that they model for their students. Then the students run their own science experiment with the guidance and support of the teacher. They learn the importance of a variable, standardized testing conditions, and the scientific method. They learn to ask their “Big Question.” They create a hypothesis or “I Think Statement.” They run tests, collect and interpret data, make “Big Discoveries,” and ultimately try to formulate some conclusions.

The process we’re trying to drive home starting in 3rd grade is the idea of a discovery. A discovery can be anything and it doesn’t have to be right or wrong, but you can’t lie. At no point are you ever allowed to go back and touch your hypothesis or your prediction about what you think you might discover. A hypothesis is just a guess. It’s what you think. The hypothesis isn’t the grade. You don’t win if you say, “Hey, I guessed it right!” I think you lose. If you say it’s going to float every time and it does (see 1st grade chapter), then you didn’t push yourself in the first place or try anything unusual. Every kid will say that a bowling ball is going to sink and when it floats, only then do they make a discovery. With the discovery comes another experiment. The scientist asks more questions, collects more data, compares it to the previous data, and sees what other questions arise. Along the way he or she makes lots of little discoveries and then finally draws some conclusions.

The process we’re trying to drive home starting in 3rd grade is the idea of a discovery. A discovery can be anything and it doesn’t have to be right or wrong, but you can’t lie. At no point are you ever allowed to go back and touch your hypothesis or your prediction about what you think you might discover. A hypothesis is just a guess. It’s what you think. The hypothesis isn’t the grade. You don’t win if you say, “Hey, I guessed it right!” I think you lose. If you say it’s going to float every time and it does (see 1st grade chapter), then you didn’t push yourself in the first place or try anything unusual. Every kid will say that a bowling ball is going to sink and when it floats, only then do they make a discovery. With the discovery comes another experiment. The scientist asks more questions, collects more data, compares it to the previous data, and sees what other questions arise. Along the way he or she makes lots of little discoveries and then finally draws some conclusions.

My ultimate goal is that when students get to 5th grade they understand the difference between discovery and conclusion. I like to compare it to watching an episode of CSI—the discovery happens about forty minutes into the show. There are little discoveries along the way, but the “big discoveries” occur close to the end of the show, and in the last thirty seconds we get the conclusion. The discovery leads you to all the things you did or thought that were wrong. When you get to the conclusion, you tie it all together. Your conclusion isn’t what you set out with at the beginning. There’s always a little twist or turn. Those twists and turns are what make the show interesting and, in a science experiment, are what keep the scientist exploring new ideas.

I like to use the acronym CCCOM to illustrate good scientific thinking. Count, compare, classify, observe, and measure. We should focus on this approach with all we do in science. If the science we’re teaching doesn’t have at least several of these ideas, perhaps we should reconsider taking the time to teach it or at least adjust the method by which we are teaching it. If a kid can’t count, compare, classify, observe, and measure, how can he or she make good decisions when he or she goes to buy a first car? How can a kid ever know if something he or she sees on the Internet is true? These are life skills we’re talking about. You have to have a little skeptic in you to be able to notice when something doesn’t feel right and to know that you should ask questions or do a little research.

This Boot Camp program guides kids through this process. It encourages kids to explore their ideas. Test them out. Were you correct? What did you discover? What would you do differently next time? What else did this make you wonder about? Did you write the conclusion in the last thirty seconds? When you get to the 5th grade level, if you’re picking the right experiment, you are asking more questions than you could ever answer. There are so many variables that there is no way you could get through them all. Some teachers fall into the mold of: “Please submit your project by such and such a date and we will analyze it to see if this is a viable project.” Why do we do that to kids? We should be encouraging them to explore their ideas and natural sense of wonder while also teaching them the skills of scientific inquiry.

We need to be flexible and run in the direction our discoveries take us. Teaching science is like jazz. I know where I’m going to start and I know where I’m going to finish. I just don’t know where I’m going to go in between. Every night I play it just a little bit different. Every time I teach science it’s going to be a little bit different. Every year you do the Boot Camp it will be slightly different. Students will make different discoveries and want to take the experiment in different directions. Allow them to do that even if it means taking a few extra days. Kids learn that their ideas matter when they are given the time to ask questions and are encouraged to pursue the answers to those questions. Boot Camp models critical thinking skills and, hopefully, prepares kids to explore ideas independently. Even if the students never choose to do a science fair experiment on their own, they will leave Wilder Elementary having completed six real science projects.

If we’re going to effect change and we’re going to model something new, it has to be hard and you have to have resistance. If you don’t, you’re just like the first grader who was always right in his sink/float predictions. Getting started with the Boot Camp program isn’t easy. Many teachers will be uncomfortable with changing they way they’ve been teaching science and with taking themselves outside of their box. We found that to be true at Wilder, but if your school has a “Pied Piper” to lead the charge and motivate the staff to try something new, we think you’ll be very glad you put forth the effort. The kids are ready and want to participate in hands-on, engaging science activities much more than they want to learn science out of a textbook. The parents are excited to hear their kids talking about science at the dinner table and recounting the awesome discoveries they’re making under the guidance of their wonderful teacher.

To be successful, however, the staff has to be on the same page. Every class in each grade level needs to do the same project and needs to share what is working and what isn’t. Each grade level needs to hear from the others what is going on in their classrooms, what successes they are having, how the kids’ thinking is changing, and what they need help with. Frequent feedback amongst the staff helps teachers know what is coming and helps them anticipate how they might want to change or extend their experiment based on what kids at younger grades have experienced. By 5th grade, the students are ready to go and the teachers have a chance to hit a home run. Give them the support they need and let them go.

My hypothesis is that over a period of time we will see an advancement not only in the kids, but also in the teachers and the parents. We just completed year five of our seven year pilot program at Wilder Elementary. I believe we are really going to see evidence of great advancement at year seven when we interview the middle school science teachers. Hopefully they will have seen growth in student background knowledge and independent thinking. We are seeing the proof that our program is working already. The teachers are experiencing “aha” moments and the kids are growing leaps and bounds in their scientific self-confidence and background knowledge. Parents are much more comfortable with the voluntary spring Science Fair because their kids already know what to do. They aren’t the ones teaching science and trying to figure out what to do and how to do it when their child says they want to do the Science Fair.

Please take what Wilder has done and adjust it for what works for you and your students. You don’t have to re-invent the wheel. Learn from the teachers at Wilder as they share their projects and progress. Now, slow down and allow kids to wonder, discover, and explore.

I’m a home school mom who is organizing our home school group’s 4th annual science fair. Unfortunately, we have very few kids signed up (20) as opposed to 34 last year. The concern is why aren’t more kids signing up? There have always been awards and prizes for the top three in each group range and plenty of notice is given to the parents regarding the date of the event. It’d be nice to have more particpants next year. Any ideas or suggestions?

Hi Steve,

I was at your science workshop today in OKC… had a blast… You mentioned that we could get the info on the science bootcamp from you…I would love it, if I could please get the information

thanks again!

Hi Janou – you can find out about the bootcamp and all of the teacher training workshops Steve does by following this link to his website: https://www.stevespanglerscience.com/teacher_training

Each event is an amazing experience!